Community Science: Supporting Salt Marsh Harvest Mouse Recovery Together

I was once in a meeting of regional scientists and managers and when I suggested that salt marsh harvest mouse (SMHM; Reithrodontomys raviventris) surveys should be prioritized as part of a regional monitoring effort, someone responded with something to the effect of, “Well, we don’t need to worry about the mouse because the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) are monitoring them.” It was in that moment that I realized just how poorly folks understand the regional monitoring situation surrounding this endangered species. Unfortunately, when it comes to endangered species, misunderstandings can have real consequences for species recovery.

One of the greatest challenges to SMHM recovery is an inability to characterize population trends due to a lack of comprehensive monitoring, spatially and temporally. Though the Recovery Plan for Tidal Marsh Ecosystems of Northern and Central California clearly outlines a step-down strategy for downlisting and delisting the species that specifically defines areas to be surveyed and required intervals, no specific person or entity is tasked with coordinating this monumental effort. As a result, survey efforts throughout the range of the species have not been completed in a manner conducive for analysis of trends. State and federal agency biologists have done their best to survey systematically on public lands under strict mandates and even stricter budgets. But, in no way are these researchers able to comprehensively survey their lands throughout the species range on a regular basis. Meanwhile, other biologists have surveyed on public and private lands when opportunities arose, but these sporadic efforts were constrained by access and research funding. Biologists who are not affiliated with resource agencies (like me!), can perform surveys only when research funding is obtained, or when an entity chooses to fund surveys, and then only with extensive permits and survey-specific permission from the USFWS.

These challenges have led to piecemeal, usually sporadic species surveys over the SMHM’s recovery history. The first effort to bring together researchers for a comprehensive rangewide survey for the SMHM occurred in 2022, about 50 years after the species was listed as endangered by the state and federal governments. A collaboration between WRA, CDFW, USFWS, Suisun Resource Conservation District, and U.C. Davis, the inaugural Salt Marsh Harvest Mouse Rangewide Survey took two years to plan but only two months to complete, and it provided the first ever snapshot of SMHM densities throughout the range. In addition to the leadership team, over 60 biologists supported the effort as volunteers and dozens of entities granted support through land access, while the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation provided funding support.

Just several months later California experienced unprecedented rainfall, the winter of 2022/2023 was the third wettest on record. Salt marsh harvest mouse biologists had long suspected that rainfall—either the timing or amount—had a strong impact on SMHM populations, and this extreme weather provided the perfect opportunity to investigate. But without the funding associated with the rangewide survey, we faced the same challenge we always have, limited resources. Biologists at CDFW were able to resurvey a handful of sites, and WRA biologists surveyed at several long-term monitoring sites, but USFWS and other entities had a very limited capacity to monitor on their properties after the extreme winter. Two such sites were Mowry Slough and Calaveras Marsh within the Don Edwards National Wildlife Refuge. These sites had the highest SMHM densities of all the sites in the South San Francisco Bay, and represented a great opportunity for follow-up surveys, though none had been planned.

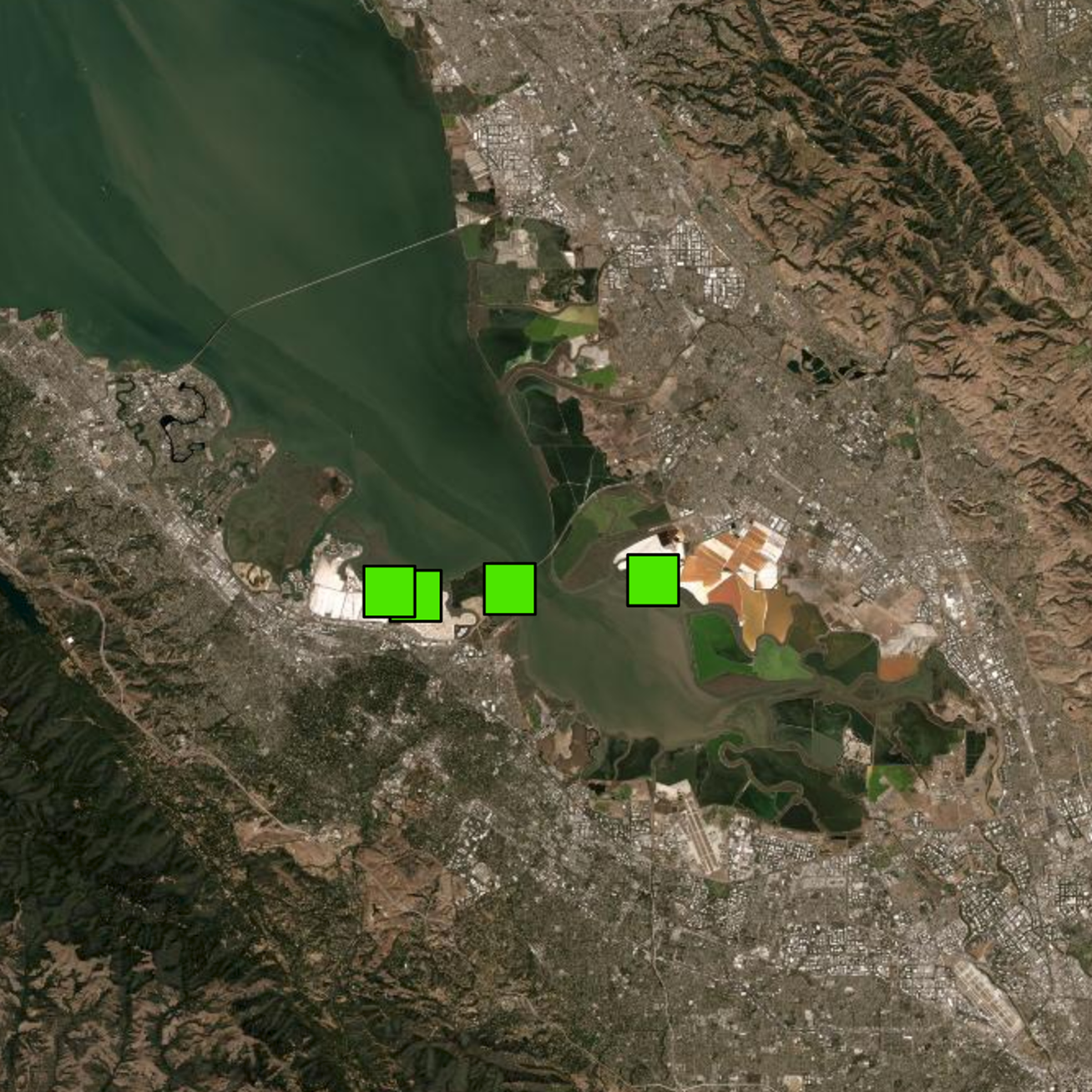

When Cargill, Incorporated contacted me and expressed interest in funding SMHM surveys in the South San Francisco Bay, we knew it would be a great opportunity to fill some gaps in the post-Rangewide follow-up. In collaboration with USFWS biologists, WRA biologists identified four areas to be surveyed with the funding. One was Mowry Slough; as one of the top three highest density sites in the entire range-wide survey, this site was an obvious choice. There was also a desire to trap at Ravenwood Slough, as SMHM had been seen there during the recent South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project work. We also identified two other areas that have not been surveyed recently, if ever: Flood Slough and the Ravenswood Shoreline at Dumbarton Bridge.

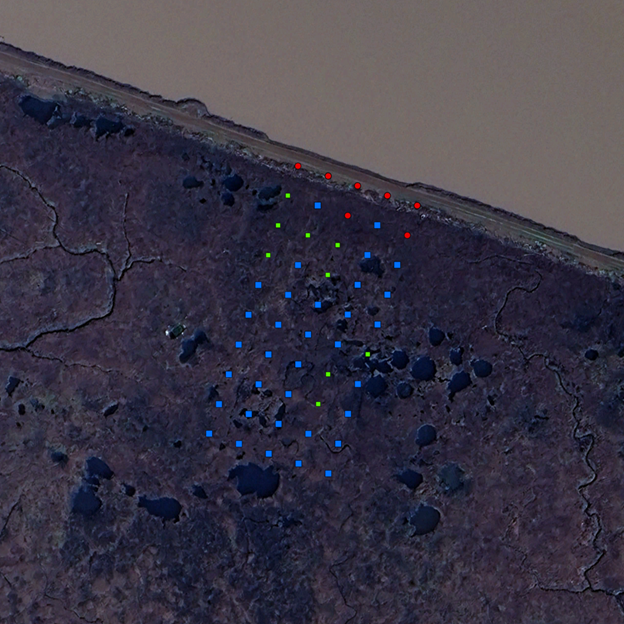

The survey was completed in late August 2024. WRA, with volunteer assistance from Cargill, USFWS, Swaim Biological, Stantec, and Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District, surveyed all four areas for three nights. At Mowry Slough, the rangewide survey grid location, consisting of 50 traps, was utilized again. At the Ravenswood restoration area, three rows of 10 were placed in a grid stretched from the remnant marsh into the newly restored future-marsh area. At Flood Slough, two transects of 10 each were placed parallel to the berm. Finally, at Ravenswood Shoreline, 10 traps were dispersed throughout the small marsh area. Across three days traps were opened at sunset and checked at sunrise, then closed again after all animals had been processed and released.

As expected, captures were high at Mowry Slough. Just about the same number of SMHM were captured in 2024 (32) as were captured in 2022 (34). The only other site that had SMHM captures was Ravenswood Shoreline, though we only caught one individual there. You might be wondering how we can compare a trap grid with 50 traps to an area with only 10 traps. Salt marsh harvest mouse survey data is often normalized as catch per unit effort. To calculate this, we divide the number of trap nights (number of traps x number of nights deployed) by the number of animals captured. For example, three nights of trapping at Mowry Slough with 50 traps is 150 trap nights. This yielded a catch per unit effort of 21%. One SMHM capture at Ravenswood Shoreline with 30 trap nights is 3%. To put these numbers in context, consider that the step-down narrative for SMHM recovery in the recovery plan requires a 3% catch per unit effort (at a high number of sites over set intervals and durations) to downlist the species, and 5% to delist. We often use these baselines for comparison. Even with only one capture, catch per unit effort at Ravenswood Shoreline equals the lower baseline. With 21% Mowry Slough exceeds the higher baseline of 5% four times over.

Unfortunately, both Flood Slough and the Ravenswood restoration area, specifically the area where the berm was lowered to expand the marsh area, had no harvest mouse captured. Both areas did, however, support high densities of house mice (Mus musculus). This is not unexpected considering the level of disturbance at both sites. However, since SMHM were seen during construction at Ravenswood restoration area, it was somewhat surprising not to detect any SMHM there. Long-term monitoring of this site would be valuable for understanding the community succession as the newly created future-marsh areas mature.

While the level of disturbance certainly impacted the composition of the species we captured at Flood Slough and the Ravenswood restoration area, the extremely wet 2022/2023 winter likely also contributed, potentially in a much less obvious way. I believe that habitat use by SMHM is more strongly driven by competition with more aggressive co-occurring rodent species such as western harvest mice (R. megalotis) and house mice than by habitat characteristics directly. Marsh areas are not water-limited, so increased rain and outflow there provides limited value, and actually poses a threat to wildlife there that must cope with extreme flooding. On the other hand, adjacent uplands—where aggressive competitors thrive—benefit greatly from precipitation through increased plant growth leading to high forage for the rodents that live there. This can result in rodent population eruptions. When densities of rodents in uplands become too high, they must disperse into adjacent habitat, even if it is less attractive. For the upland associated rodents in the San Francisco Estuary this may mean moving down into the marsh.

We know that SMHM populations were negatively impacted by the heavy winter of 2022/2023; the site with the highest captures during the Rangewide survey in 2022 had no SMHM during a follow-up survey at the same location in 2023. However, populations generally were recovered by 2024, but not to the same degree at all sites. At sites that did not have extensive adjacent uplands, populations of SMHM were much closer to 2022 levels (if not higher) than sites abutting uplands. This pattern is well illustrated by the survey we are reporting here. At Flood Slough and the Ravenswood restoration area no SMHM were captured, and densities of house mice were high. Both of these areas abut Bedwell Park which consists of about 175 acres of upland grassland habitat. Don’t forget, SMHM had been seen at the Ravenswood restoration area in late 2022, before the restoration and wet winter. But in 2024 they were gone.

On the other hand, the two sites where we did detect SMHM, Mowry Slough and the Ravenswood Shoreline at the Dumbarton Bridge, had very little adjacent upland grassland habitat. What was present was represented only by narrow strips on levee sides. This may be hard to reconcile as it’s commonly believed that extensive adjacent uplands are vital for SMHM to persist during extreme tide and flooding events. However, recent research indicates that SMHM do not commonly use uplands as refuge during extreme flooding events, and that these grasslands can harbor high densities of upland associate rodents that can compete with SMHM and potentially depress population recovery following stressful periods such as the 2022/2023 winter.

While further monitoring and data analysis is necessary before we can come to any definitive conclusions about the interactions between SMHM, competing rodents, weather, and regional habitat, this survey effort—and others that WRA and entities like CDFW have undertaken following the 2022/2023 winter—certainly supports a conclusion that physical habitat characteristics may not be the largest driver of SMHM habitat use, and potentially survival.

WRA is thrilled to have partnered with Cargill to complete this survey. This investigation, along with all SMHM survey efforts in the past five years or so, highlights the necessity of regular and repeated monitoring efforts throughout the range of the SMHM to account for natural population fluctuations, and to tease out what factors are driving them. If you are a landowner, and you have been considering supporting a SMHM survey on your property, know that this data would not only inform your understanding of your property but also will fundamentally contribute to our knowledge of this endangered species. The impact of your support can extend well beyond your fence line!

ksmith@wra-ca.com