Steelhead Migration Restored in a Napa River Tributary with Removal of a Century-old Dam

In the year 1900, in the small Napa Valley town of St. Helena, increasing water needs for agricultural and municipal uses prompted the St. Helena Water Company to build a 45-foot high earthen dam and water storage reservoir above the town on York Creek, a pristine mountain tributary to the Napa River. A newspaper account at the time boasted that the project would supply residents with “fresh water absolutely pure.” However, in addition to holding back streamflow, the dam blocked a thriving population of native steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss) from reaching high-quality spawning and rearing habitat in the upper 1.5 miles of York Creek.

For the past 120 years, a diminished steelhead run has persisted in the lower portions of the stream, prevented from ascending past the dam and into York Creek’s headwaters. There, deep pools of cold water and dense forest cover provide ideal conditions for young fish to feed, grow and shelter from predators during the hot and dry Napa summers, in preparation for the seaward journey juvenile steelhead make after one or more years in freshwater.

Since 1997, the handful of steelhead hanging on in York Creek, part of a larger Central California Coast population group, have been federally listed as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act. The National Marine Fisheries Service recovery plan for the species called for the removal of the Upper York Creek Dam and a number of other fish passage barriers in the region. York Creek’s story is not unique, and in recent years, citizens, communities and government agencies have begun to weigh the costs of maintaining unneeded or defunct dams and other barriers with the value of restoring healthy stream systems connected to their headwaters.

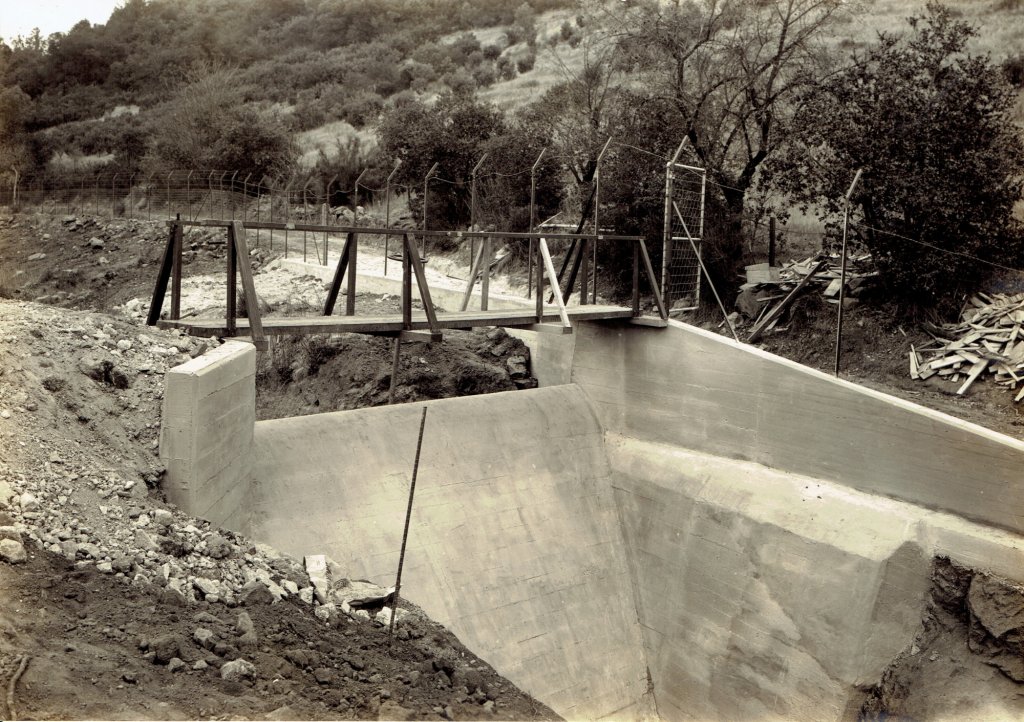

Today, after more than 25 years of planning and regulatory pressure, the City of St. Helena, in partnership with federal and state permitting and funding agencies, has removed the earthen dam built by its industrious citizens over 100 years ago. What once seemed like a permanent feature on the landscape has now become a part of York Creek’s history. This dam itself, however, was only a portion of the 22,000 cubic yards of sediment removed to unbury York Creek’s historic channel and restore a naturally functioning stream. Since its construction, the dam had not only blocked the upstream migration of steelhead, but also the downstream movement of sand, gravel, cobble and boulders in winter storm flows. Sediment had filled the reservoir to depths of up to 29 feet, eliminating its water storage capacity entirely by the year 2000. Because the dam blocked the natural flow of sediment that replenishes steelhead spawning beds, habitat conditions in downstream areas had deteriorated significantly.

A number of dam removal designs and projects were proposed over the past two decades, but it wasn’t until very recently that a workable solution finally emerged. In 2019, WRA, Inc. was selected by the City’s primary contractor, EKI Environment & Water, Inc., to complete engineering, hydraulic and habitat restoration design as well as all permitting for the Upper York Creek project. With the support of numerous consulting, funding, and regulatory partners, WRA staff played a key role in bringing this important restoration project to construction.

Many complex and challenging technical and permit requirements made the $6,000,000 project to excavate the dam and restore York Creek considerably more difficult than the original “waterworks,” which were built with just a $5,000 bond (in 1900 dollars). The challenges included a short construction period to avoid harming nesting birds, amphibians, and migrating steelhead that are present seasonally; engineering, construction and budget constraints; and exacting regulatory specifications from multiple agencies.

For more than a year, WRA’s design and permitting staff worked to complete final plans and obtain permits for this high-profile project. The design team, led by Andrew Smith, PE and former colleagues Brian Bartell and Ben Snyder, PE, modeled every aspect of the work to create restoration plans that met every requirement and could be carried out by the contractor working on the site. To begin to improve the downstream reaches of York Creek, a strategy was finalized to excavate a large part of the impounded sediment, but to leave some of the gravel and rocks, to move naturally with streamflow and restore degraded habitat over the next few rainy seasons. The team, with oversight from geomorphologist Virginia Mahacek, also designed 36 bioengineered log structures that have been placed carefully in the stream below the former dam site. These “habitat complexity” features proved to be a crucial element in the restoration project, as they are expected to capture and hold in place some of the beneficial sediment left in the stream channel that will cascade down with the first big stormflows. The structures will also trap branches and leaves, forming thick underwater tangles that young steelhead and other species seek out.

WRA regulatory and biological staff, including Amy Parravano, Brian Freiermuth, and Erik Schmidt, expedited and completed the permitting process, coordinating and submitting applications to all State and federal agencies to ensure that permits were issued for construction on time – and following up with monitoring so all permit requirements were met. Biologists Stewart DesMeules and Nick Brinton relocated 103 juvenile steelhead from a small pool and wetland area below the dam, and 29 resident rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss that are unable to migrate to the ocean) from the marshy, sediment-filled reservoir area above the dam, so they would not be harmed during construction.

In this highly impaired, yet resilient watershed, the presence of native anadromous steelhead and a relict native rainbow trout population long isolated above the dam is a true testament to the importance of restoring York Creek for this threatened species of fish. With strong support from the City of St. Helena, the National Marine Fisheries Service, state and federal grant funding agencies, and many others, major construction work to remove the dam and restore the waterway was recently completed, while revegetation with native riparian plants and biological and other scientific monitoring will continue into the future at the restoration site. Although the destructive Glass Fire tore through the area just days after project completion in early October, possibly damaging some of the key habitat features (an assessment hasn’t yet been possible due to road closures), all the restoration partners are determined to get past this unexpected setback.

As late fall and winter rains sweep the Napa mountains in the coming months, York Creek will flow freely through the former reservoir and dam location for the first time in more than a century, passing the log habitat structures installed downstream before finally merging with the Napa River. Steelhead are expected to soon swim upstream to find ideal spawning grounds that were inaccessible for years to these magnificent and strong fish. If the engineers and workers who created the original water storage system, touted at the time as “one of the most complete in the State,” were here today, they would likely appreciate the enormous technical, financial, and logistical challenges that were overcome in order to remove the very same dam they built so long ago. In addition to those who have a stake in the region’s present environmental health, the Upper York Creek Dam’s pioneers might well marvel at the reconnection of a broken watershed. This very special project ultimately links us across time.

To read more about this project, please visit the City of St. Helena’s website.